Queer Tamil

Collective

Land Acknowledgement

The land in which Queer Tamil Collective is located has been the home of Indigenous people and Nations long before colonial documentation of time and is specifically the land of the Wendat, Anishnabek, Mississaugas of the Credit, and the Haudenosaunee. The territory of what is known today as Toronto is under the One Dish, One Spoon Wampum belt, a peace treaty between the Haudenosaunee and the Anishinaabek, and is a mutual agreement between nations for sharing land and resources. The territories that encompass Toronto, as well, are under a number of Treaties including Treaty 13, and in Toronto specifically the Williams Treaties. There have been many Indigenous names and words associated with this place, and today, Toronto is home to a multitude of Indigenous people, languages, and cultures from around the world.

We as an organization are composed of people from various walks of life. All of us at QTC encourage you to support and advocate for Indigenous people and communities, everywhere. In Canada, specifically, this can look like many things; such as actively returning land, rejecting government legislation that violates the rights of First Nations, Inuit, and Metis people, denouncing colonial histories within institutions, ending violence against Indigenous women, Two-Spirit, and girls, donating money to Indigenous youth groups, and any actions that genuinely support the wellbeing and success of Indigenous people, everywhere.

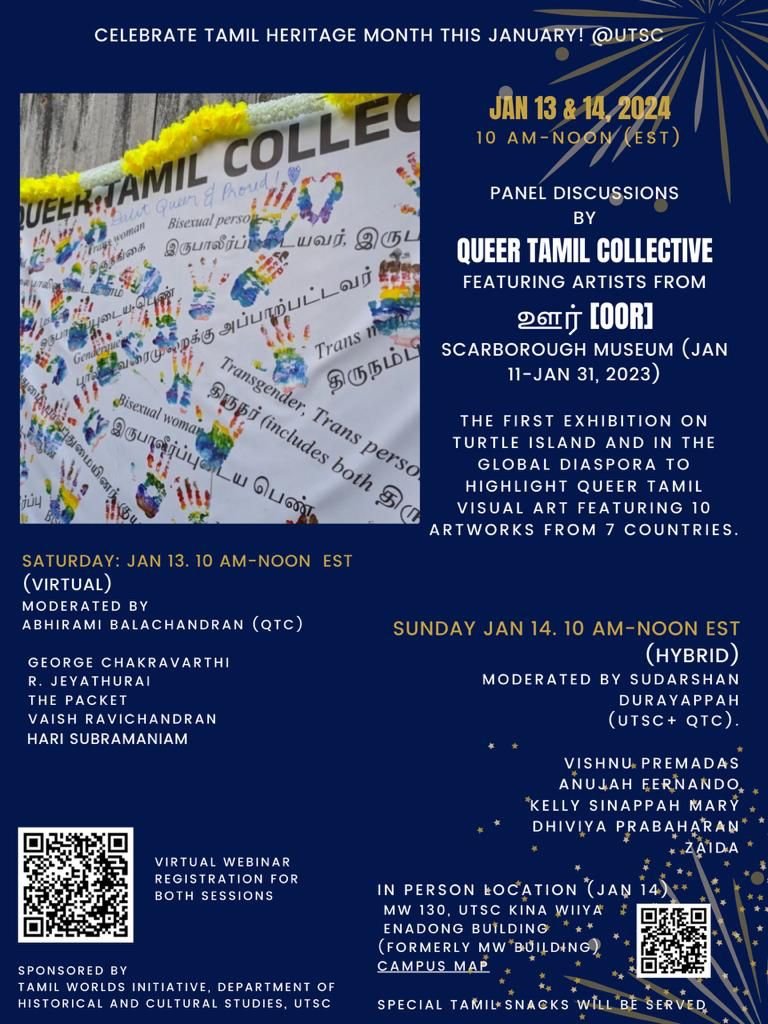

Celebrating Tamil Heritage month this January! @ UTSC

Panel Discussions by QUEER TAMIL COLLECTIVE Featuring artists from ஊர் (OOR). Jan 13th &14th 2024 10am to noon (EST)We remember our Queer Tamil Stories of Black July

QTC is proud to share!

QTC is proud to share!

QTC is proud to share that all three ஊர் Exhibition art workshops have been sold out. Congratulations to QTC artists Dhivya, Zaida and Vishnu.

Many Thanks to the Scarborough Museum, Madalen and Abhirami.

'It's never happened' before: Queer Tamil Collective exhibition at Scarborough Museum is first outside Sri Lanka

The gaze that draws you to the reclining figure between the curtains has a name.

George Chakravarthi’s "Self-Portrait As An Unknown Devadasi" arranges the London-based artist on a bed to evoke the sort of voyeuristic photographs taken for colonizers in India.

Chakravarthi in this image is depicting himself as a devadasi, a traditional class of “affluent temple dancers and preservers and protectors of the arts” which didn’t survive colonization.

“He’s extremely famous in Europe, very shown in all the big galleries,” said Sudharshan Duryappah, part of Toronto’s Queer Tamil Collective.

Yet Chakravarthi has never been in an exhibition in which all the artists are queer and Tamil.

Apparently, apart from participants in a single show in Jaffna, Sri Lanka, no one has.

“It’s never happened in France, never happened in New York, never happened in Zurich,” said Duryappah, the creative and artistic lead for Oor, the QTC Pride Exhibition which launched in June at Scarborough Museum.

The history-making exhibit will run through the end of January, Tamil Heritage Month, and brings out the porous nature of identity and sexuality, which is “not a sealed Tupperware,” he said.

Many Scarborough residents are conservative on sexuality, but the collective wanted the exhibit there because Scarborough is where most of its membership lives.

“This work being here is also empowering for the artists,” said Duryappah, who hopes Oor could later tour.

In the museum’s Kennedy Gallery, Chakravarthi’s work hangs close to the work of queer Tamil artists living in countries where homosexuality is still illegal (Malaysia, Sri Lanka), and in Singapore, where it was decriminalized only last year.

Being at the museum, in buildings and around furnishings from the 19th and early 20th centuries, the show is also “direct commentary on how people of colour take up space in colonial institutions,” Duryappah said.

The museum in Thomson Memorial Park, however, supports QTC and last year hosted the group's inaugural Tamil queer event in Canada where they created a banner for the Toronto Pride celebration along with pronoun-declaring buttons in Tamil and English for the 2022 festival.

Besides excellence in queer Tamil visual art, the exhibition shows intergenerational trauma caused by repression. In particular, it shows the effects of Black July, a 1983 anti-Tamil pogrom which set off a wave of migration to Canada, creating the largest Tamil diaspora outside South Asia.

Hanging over a window in Cornell House, another museum building is Oor Pogum Megankal, or “The Clouds That Go Home” by Dhiviya Prabaharan.

Born in Canada and an undergraduate at the Ontario College of Art and Design, Prabaharan used batik on fabric to recall “the calm of a nine-year-old boy, my uncle, and a 13-year-old girl, my mother” in their grandmother’s embrace as they travel to safety by boat after the horrors of Black July.

Many people displaced by the pogrom moved away on boats, said Abirami Balachandran, the exhibition coordinator. “The piece speaks to being between the clouds and the sea.”

Oor, she said, is “a multifaceted Tamil word that could mean location, village, home and identity.”

The goal of the multi-layered exhibition is to continue a dialogue where queer Tamil people “can feel seen in ways we want to be seen” and can express ourselves, Balachandran said.

An artist panel is planned for the last quarter of 2023 and the collective is hoping for more programming opportunities at the museum.

The exhibition’s poster was designed by Marvin Veloso from a pencil drawing, “1,2”, by Andil Gosine and Kelly Sinnapah Mary, of a rooster in heels. This work is also part of Oor.

A QR code on the poster provides a link to the City of Toronto’s mental health resources because of the mention of genocide, displacement and violence.

Correction — July 10, 2023: This article has been edited from a previous version that mistakenly called the exhibit at Scarborough Museum first of its kind in the world. It is in fact the first exhibition featuring queer and Tamil artists outside Sri Lanka.

I’m queer, and from an ‘untouchable’ caste. In Canada I had to come out of the closet twice

I grew up in India. I knew I was queer in India, but I couldn’t come out, like it wasn’t a safe space. I moved to a safer country. I used my privilege of having an education to move to Canada.

Now I work here. I came out as queer as soon as I came to Canada. But I’m not out to my immediate family. They have so many issues to deal with. It’s hard for them to understand.

I’m not religious, but my family is Christian. If you go to the church they know which caste we are. Oh, yes, the churches are also divided. It’s not endemic to one religion. In Christianity and Islam, even in Buddhism there’s casteism. In India, we can’t go to the dominant caste church.

You wouldn’t be welcomed. They know (our caste) when they ask my parents’ name. And they’ll ask which town I come from. Which church. In Christian circles, church is a marker of caste. Which city you come from is also a marker.

In Catholic churches, the seating is divided, and dominant-caste churches, like most churches, are planned in the shape of a cross. One part of the cross is for choir, another is for oppressed castes (Dalit and Adivasis). Another one is for dominant castes and another one is for the backward caste (Shudra). It’s not written, but you know.

The whole idea of turning to Christianity was to escape from casteism. But people who converted still came with the ideas of casteism into the church.

In altar communion, you go to the front, and they give you some wine in the chalice. But they have switched that custom to individual cups. So you’re not sipping from a cup that’s been sipped by a Dalit person.

When I moved to London, Ont., I wasn’t out in university. I was out as queer in certain community spaces. But I wasn’t truly free.

In the queer community, there was racism.

They would have a stereotype of a brown person: “brown guys smell, they’re not clean,” that sort of stuff. And while dating or meeting people, you could be denied. You could be unfriended because of the race identity.

So I moved to Toronto, to find a safe space. And in Toronto there are more brown people, and in the diaspora, I’ve found queer spaces. I can be proud, I can be queer.

But I could not be Dalit.

They would talk about beef-eating in a certain way. Because eating beef is a caste marker. Even pork-eating is a caste marker.

I’ve had this experience with friends that would use this casteist slur “pariah.”

They would attach the pariah suffix to body parts, to the female body parts that I don’t want to say here. Or they would say pariah dog (in Tamil).

I mean if you They would attach the pariah suffix to body parts, to the female body parts that I don’t want to say here. Or they would say pariah dog (in Tamil).

I mean if you google the word it says pariah is one who is of a lower caste. What did we do to be lower? We just live.

That’s when I came out as Dalit. I couldn’t tolerate them saying this (pariah) constantly. I said, ‘Look, I’m from this caste, and you cannot say that word but because it’s derogatory on many levels. a) It’s casteist and b) it’s sexist.’ Then a few understood and a few didn’t say it again after that. But for some it’s still a process.

And now, even in the WhatsApp groups, in the community space, I openly tell them my identity and I’m not scared of being out. Even if they bully me, I can stand my ground and I can talk for myself because I’m not scared. And I have allies who would support me on this in those groups.

Once I came out of the closets, I have a much liberated feeling that that I just can’t explain.

it says pariah is one who is of a lower caste. What did we do to be lower? We just live.

That’s when I came out as Dalit. I couldn’t tolerate them saying this (pariah) constantly. I said, ‘Look, I’m from this caste, and you cannot say that word but because it’s derogatory on many levels. a) It’s casteist and b) it’s sexist.’ Then a few understood and a few didn’t say it again after that. But for some it’s still a process.

And now, even in the WhatsApp groups, in the community space, I openly tell them my identity and I’m not scared of being out. Even if they bully me, I can stand my ground and I can talk for myself because I’m not scared. And I have allies who would support me on this in those groups.

Once I came out of the closets, I have a much liberated feeling that that I just can’t explain.

Resource : https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2023/04/15/im-queer-and-from-an-untouchable-caste-in-canada-i-had-to-come-out-of-the-closet-twice.html

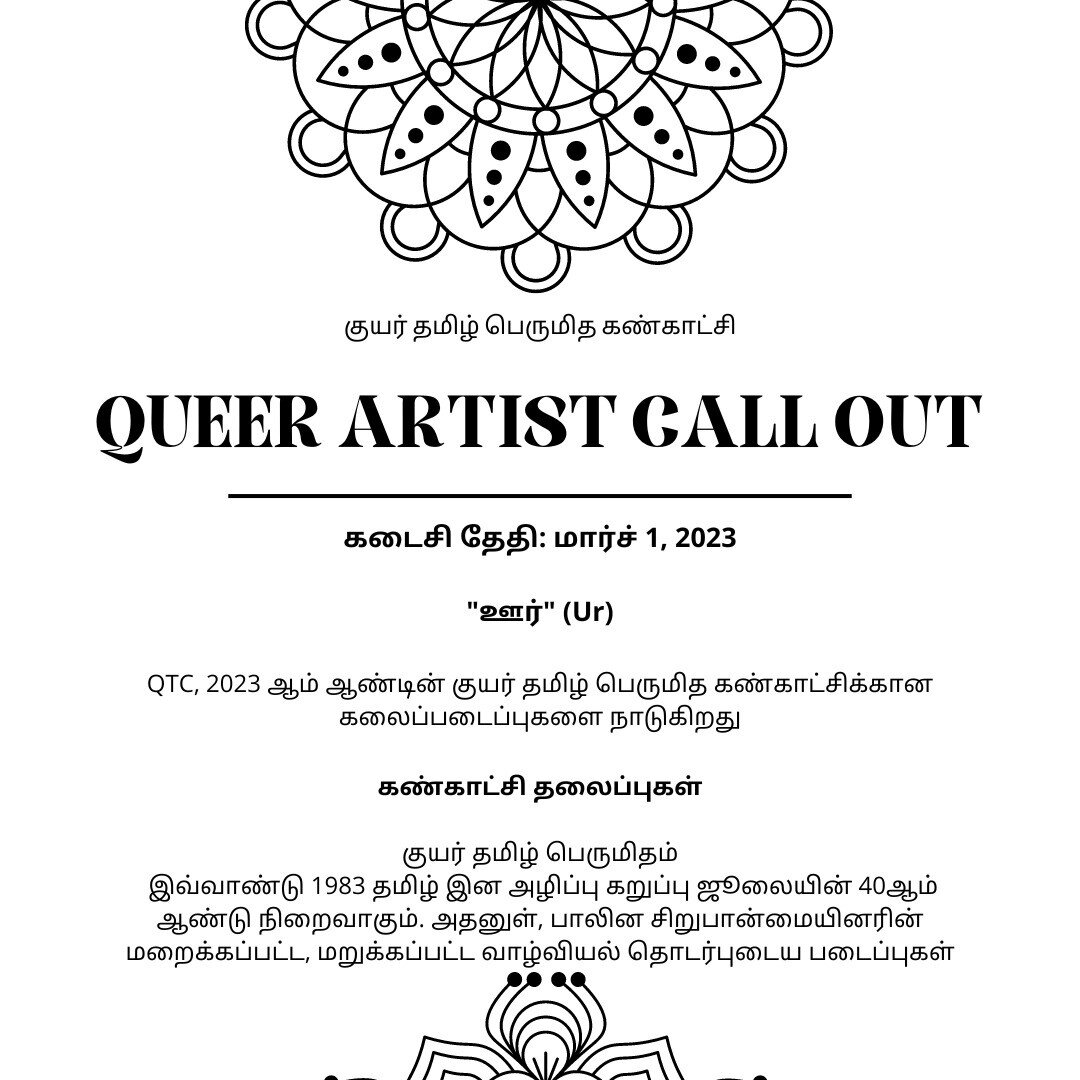

We have some exciting events planned this year, and we're looking for Queer and Trans Tamil people to help us bring our dreams into reality.

Check us out on Instagram!

Community Guidelines

✴︎

Community Guidelines

✴︎

Community Guidelines ✴︎ Community Guidelines ✴︎

being a decent human being is mandatory here

Be Kind.

We will not tolerate any transphobia, homophobia, body shaming, racism, Casteism, colourism, sexism, ablism, or any other forms of discrimination.